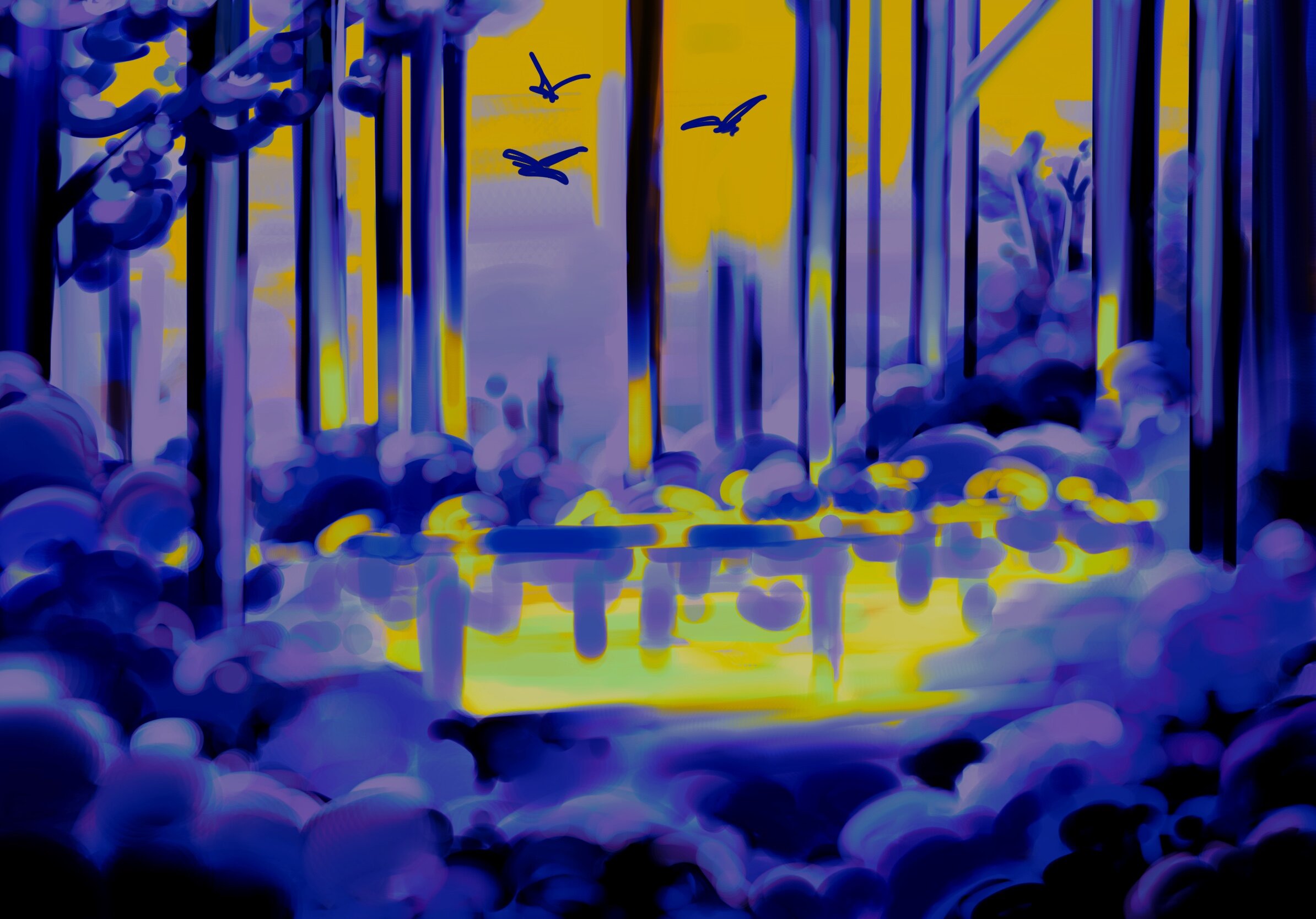

The Hawk

Illustrated by Victoria Cheng.Monday

I saw the hawk today.

He burst out of the hedgerow beside Hollow Wood, as though fired from a gun. I watched as he raced across the field ahead of me, rising hard and fast over the opposite hedgerow before disappearing from sight.

“Kestrel?” I said tentatively, knowing I was wrong.

“Don’t be a fool,” said Ted, spitting his fag butt into a puddle, where it sizzled pathetically for a moment before sputtering out. “Sparrowhawk.”

“How d’you know?”

“The sparrowhawk keeps low. Moves from hedge to hedge. Kestrel stays higher, ‘n hovers. Doesn’t matter too much really. All pests, in my view. Waste of space.”

I said nothing, only grunted and brought the fence knocker down as hard as I could onto the stake. It sunk into the soft earth easily enough, but I brought the knocker down once more. I felt the impact of it through my shoulders. It felt good.

“Trying to knock that stake down to Australia?” Ted asked. He laughed at his own feeble joke and then coughed, hard.

I pulled the knocker off, motioned to Ted. He squelched the short distance to the trailer, pulled a stake off it, and walked back to me.

I knocked it in with just as much force as the last one. I was annoyed with myself for not knowing that it had been a sparrowhawk. It should have been obvious enough.

“Something the matter?” Ted said warily.

I looked at him – water dripping from the peak of his old cloth cap onto the end of his beak-like nose. Fag packet stuck in the pocket of the old colourless coat he wore every day. Faded cords tucked into the wellingtons I had given him years ago. He took a cigarette from the packet, stuck it between thin lips and lit up. His weathered face took on a look of contentment. Suddenly I couldn’t stand him.

I looked at my watch. “It’s nearly half-five, Ted. You can get on.”

He nodded. “See you tomorrow then,” he said. He shoved his hands into his pockets and sloped off out of the field, down the lane to his cottage and wife. Both were as dishevelled as him.

He gave no thanks for the early finish. I watched as his head bobbed along the other side of the hawthorn. Once he was out of earshot, I spat a fat wadge of phlegm in his direction.

“Useless cunt.”

I turned back to the fencing. It would take another couple of hours at least, more now that I had sent Ted home.

Linda would be waiting. Some stodgy pie or stew would be cooking away in the oven. Let her wait. Let the food stew. I had to work. Not that she seemed to understand that.

The fence stakes had grown rotten and loose in the ground. Luckily, most of the field was bounded by an old hawthorn hedge – planted in my great-great grandfather’s time, Dad had always said – but the section which needed repairing was still substantial. I wanted to get all the stakes in tonight, and then Ted could get the rest up over the next few days while I began drilling.

I had already taken off my coat when Ted and I began, but as I went along the edge of the field, hammering in the stakes, the exercise and my fury – at Ted, at my own lack of knowledge – meant I was soon sweating away. I took my jumper off and hung it on a stake.

It was in this state – red and sweating, in my shirtsleeves, doing a labourer’s job – that Adams found me. He came rumbling along down the lane in his new John Deere. No trailer, no drill, no plough. Just driving it for the sake of driving it. I felt sure that he was showing off, letting all and sundry know how well he was doing.

Adams waved when I looked up, and I raised a hand in return. “Don’t stop and talk,” I growled, but he did.

“Alright, Dan?” he called, after he had cut the engine and jumped down onto the damp verge.

I nodded. “Fine thanks.” I could see him looking me up and down, judging my filthy boots and trousers and my unwashed shirt. The only dirt on him a spattering on his boots, most likely picked up when he got out of the tractor. Easy enough to stay clean, when you have as many labourers as he does, and a farm manager.

“Shame about all this rain,” he said. His voice and face were all friendly, but I was sure that there was some mockery in there somewhere. He was laughing at me.

But I wasn’t going to fall into his trap. No. I didn’t want to seem all friendly. That was how he would get me, how he would ask how I was doing, whether I wanted to rent out some of my fields to him. I knew his game well enough. “A shame,” I replied, keeping my words guarded. “Start drilling tomorrow though.”

He looked up at the grey autumn sky, put his hands on his hips. “We got going last week. Good drainage, my way.” He paused for a moment. The wind shook the trees of Hollow Wood. “You want a hand? It’ll be getting dark soon.”

I looked at him, frowned, showed I wasn’t being taken in by any of his false friendliness. “Not busy yourself?”

Adams shook his head. “Some of the boys are finishing up at the yard, but I’m not busy, no. Was just bringing this monster back from having a few repairs.” He gestured at the shining new tractor behind him. “Could do with a bit of exercise, to be honest.” He walked over to the trailer, picked up a stake.

“It’s fine,” I said. “It’s my job to do.”

“Couldn’t Ted have done it?” he said.

“It’s my job,” I said angrily, and felt even angrier afterwards for having let Adams get to me. He wanted this, I was sure.

“Alright,” he said. “I’ll be off then.” He was still friendly. He turned and walked out of the field up to his tractor. “Oh look,” he called from the cab. “A sparrowhawk.”

I turned and caught the last flash of the hawk. I kept an eye out for it as Adams closed the cab door and the tractor rumbled off behind my turned back. I was sure that Adams would have waved goodbye if I had been facing him, but I wasn’t going to give him the satisfaction.

It was eight by the time I had finished putting the stakes in. I had lost the light not too long after Adams had buggered off. Just my luck that it was a cloudy night. Some time in the moonlight would have served me well. Instead I had to stumble around in the glare of the tractor’s headlights, which hurt my eyes every time I turned around.

Once the job was done, I pulled my jumper over my sweat-soaked shirt, and clambered into the cab. I looked at the row of newly planted stakes and wondered what the sparrowhawk was doing. I had a sudden urge to be him, to fly low to the earth, to clutch prey in my talons, to spill blood. I felt a saltiness in my mouth, and realised I had bitten my own lip.

This sudden urge unnerved me a little. It had gone beyond my usual feelings, darted into something new which I did not understand. Eager to escape it, I started the tractor engine and drove out of the field.

Once I had taken the tractor back to the yard and parked it up in the old barn, I made my way to the farmhouse. The kitchen light was on, but the rest of the house was dark. I swore. Linda would still be in the kitchen, then.

The last thing I wanted when I came through the door was the bastard dog barking, and Linda bloody smiling at me. She looked her best – always did – and I felt suddenly very aware of my own appearance.

“Down, Sonny,” I said to the collie as he rushed up to greet me. I gave him a little kick in the ribs as I knelt down to unlace my boots, just to show what I thought of him.

The back door opened straight into the kitchen and I felt Linda’s gaze on me as I untied my laces.

“How was your day?” she asked. She smiled, which made her even prettier. I became even more aware of my sweaty and dirty appearance.

“I need to wash,” I said, walking through the kitchen to the staircase. I felt her gaze on my back.

“Eat first,” she said, all gentle. “I don’t mind you being dirty, Dan. You know that.” She set a plate of steak pie and roast veg on the table. “Eat first,” she said again.

“Well I mind it,” I replied, letting a bit of growl into my voice. I didn’t want her being nice. I sat down at the table, took the knife and fork she offered me. I ate some of the pie. “Meat’s too dry,” I said.

“I know – I’m sorry. But you said you would be back by seven. It was perfect an hour ago.”

“So I should have just left that fencing then, should I?” I snapped.

“Course not, Dan,” she replied, a bit surprised at my anger. “But you told me when you would be back, so I cooked your dinner for then. You could have come back and told me you would be late, or sent Ted.”

“Don’t talk to me about Ted,” I said, and let her know what I thought of him.

“Why don’t you let him go then?” Linda asked.

I had already had enough of her by this time, so I didn’t reply, just ate my dinner. The meat was a bit dry, but the rest of it was very good. I wasn’t going to tell her that though. She didn’t deserve the satisfaction. I emptied the plate and then shoved it away from me.

“Why don’t you let Ted go?” Linda repeated. “He doesn’t work hard enough, he gets on your nerves – why do you keep him? I’m sure you could find someone better.”

She was right – Ted didn’t work hard enough, and he did annoy me. I could find someone better. But Ted knew the farm better than anyone else, even me. He was a part of it. “I can’t let him go,” was all I said. I was too tired to explain. What did she understand anyway? Ever since I married her she had tried to worm her way into all the goings-on of the farm. Even had the nerve to tell me I was in debt – as if I didn’t already know that. We had had a good old row that evening. Hasn’t stopped her from still going through the accounts whenever she fancied it.

“How was your day?” she asked again, taking my empty plate away and placing an apple in front of me. I took a bite, but it was all soft and mealy inside. I put it down on the floor for the dog.

“Something wrong?” Linda asked, all innocent.

“You gave me a bad apple,” I growled. I felt sure she had done it to get back at me.

“I didn’t, Dan.” She went into the larder, came back with another apple and a bottle of beer. “Here,” she said, putting them in front of me. I took my pocket knife out and cut the apple up. It was alright inside, so I ate it slowly as I could.

“How was your day?” Linda asked again.

“Fine,” I said as I stood up and left the kitchen. I knew that I should ask her how hers had been, ask what she had done. But if I did it would feel as though I had lost in some way and I didn’t want that. I felt bad about it, truth be told.

I dreamt of the sparrowhawk as I slept. It flashed across the field, and I wished I had its power. And then I was the sparrowhawk. I pushed off from a branch with my talons, felt the pent-up power of my wings and body. Then I was flying across the field, my eyes fixed on the robin sitting on the opposite fence. I braced myself.

And then I woke. The morning light was grey and watery. I didn’t want to face the day, but eventually I forced myself to get out of bed. Time waits for no man, I thought, and wondered where I’d heard that before.

Saturday

I spent the next few days drilling. I would start as early as I could, but the job still seemed endless. I’d have my lunch at the farmhouse. Linda would make me sandwiches and hot sweet tea, and if it was an especially bad day I would have a bottle of beer too. It calmed me down a bit. Sometimes Linda and I would talk, as though things were almost normal. I wouldn’t admit it to her, but it felt good not to argue for once.

I wasn’t going back to spend time with Linda, mind. I was going back because I didn’t trust Ted to do the fence well enough without me keeping an eye on him. I had to pass him going to and from the farmhouse, and while he wasn’t a bad fencer, he always needed watching.

This slowed the drilling down, and at times Linda’s words about replacing Ted with someone else passed through my mind. If I had someone more reliable working for me then it would mean less time wasted.

But I was lying to myself. It was not because of Ted that I stopped by the field next to Hollow Wood so often. Really, it was the hawk I wanted to see. Since my dream, it was never far from my thoughts and I felt a yearning to see it that at times was like an aching in the chest. I wanted to confirm that it was as fierce as I recalled it. At the same time I was scared, in case it was not.

On Thursday afternoon Ted finished the fencing. I could have set him on to cleaning machinery still dirty from harvest but any time spent in his company brought a fury upon me. Before the hawk, I had always put up with him, learnt to tolerate his shortcomings because – as I had told Linda – he knew the farm and the land so well. Since the hawk, he was more of an irritant to me than Linda herself.

So I sent Ted home early on Thursday. He squinted at me suspiciously when I told him but didn’t say anything. I watched him walk out of the farmyard, and then spat as he rounded the corner.

Once he had gone, I brought the hose and brushes out of the workshop and began washing down a grain trailer I had brought round earlier. Halfway through I held the hose too close and soaked myself.

Suddenly full of a reddish, quivering rage I lashed out at the side of the trailer. I grunted at the pain, and looked down to see the skin on one knuckle split and the rest rapidly swelling up. It had felt good though, this release of blood, even if it was just my own.

I watched the water from the hose run down the sloped yard into the drain for a few moments, and then walked over to the tap and turned it off. I had no desire to work anymore. I was falling behind when I couldn’t afford to, and doing things like sending Ted home and then not working myself was going to make things worse. But I was locked into something I couldn’t get out of.

I left the farmyard and went out onto the lane. The hedgerows seemed to press in on me, hastening me along the road to Hollow Wood. I opened the gate to the field and stopped to look at the fence. Ted had done a reasonable job but this didn’t do much to please me. I felt the anger still simmering through me, the frustration, and I felt that only one thing could sate it.

I stood there for an hour before I saw anything. As I stood waiting, my clothes went from wet to damp, and I began shivering. I should have changed before I came out, or gone back to the farmhouse instead of waiting. Not that knowing this made me do anything differently.

I stayed where I was, feeling the autumn cold creep through my clothes, my skin, my bones. My teeth chattered and I started shivering. I put my hands under my armpits to try and warm myself up, and started pacing around the headlands of the field.

There was still no sign of the sparrowhawk.

It began to get darker, the autumn day reaching its end. The sensible side of me said I should go back home. But my anger said otherwise. I had to stay, had to see the sparrowhawk. I couldn’t be satisfied. I fixed my eyes on Hollow Wood as I walked, scanning the old beeches and oaks. Sometimes I imagined the shape of a hawk in the branches. It was never the real thing.

A shout from the other side of the field made me look over. A man was leaning against the gate, one arm raised in greeting. It was Adams. I looked at him for a moment, and then slowly walked over. I didn’t want to talk to him. He should have known better than to bother me. I slowed my pace even more. Might as well keep the bastard waiting.

“Alright, Dan? What are you doing?” he called as I got close.

I didn’t speak for a moment. “Just looking for that sparrowhawk,” I said. “Thought I’d have an afternoon off,” I added. “Been drilling all week.” My voice sounded defensive, and I felt a spurt of anger at myself for being so. I didn’t need to make excuses to the likes of Adams.

He smiled, and said “I wanted to talk to you about drilling, actually. I was just on my evening walk and was going to come and see you at the farmhouse.”

“Saved you a walk then,” I replied, frowning. Why would he want to come to the farmhouse? I would’ve thought it was far too messy, far too run-down for the likes of him.

He nodded. “I saw you out near me the other day. That old drill of yours can’t be much good.”

He was right. I’d had the drill for years. It needed constant maintenance and repair, and was the bane of my life. “It does alright.”

Adams looked sceptical. “It must need a lot of repairs?”

I shrugged.

“Well I’m looking to sell on my Bamlett,” Adams continued. “Thought I would give you first refusal. Mate’s rates too.”

I looked into his eyes, searching for the deceit that I knew must be there. I couldn’t see any, but I knew there must be a catch to it. “Maybe,” I murmured.

He nodded, and put his hands on his hips. “Well, I’ll give you a few days to think about it. It can’t wait forever, but I’m happy to hang on for a friend.”

“I’m not some charity case,” I growled.

He looked confused. “I didn’t think you were.” He had a small nick on his cheek from where he must have cut himself shaving, and he rubbed it. “Just trying to help, Dan, that’s all.”

I grunted. Something wasn’t right about this, I was sure. I just couldn’t think what. The shivers came back on me at that moment. Standing still again had taken its toll.

If Adams noticed this, he didn’t say anything. He nodded towards Hollow Wood. “Any sign of that sparrowhawk then?”

“No.”

“Don’t know why you’re so interested in it. Birds are birds, aren’t they? Good for target practice and that’s about it.”

I ignored him. I felt like he had exposed something ugly, and it was almost as though it were hanging in the air between us. The urge to hit something returned.

Instead, though, I turned my back on him and walked away.

“See you then, Dan,” he called.

I raised a hand in response.

“Let me know about that drill!”

I kept ignoring him. I sensed him walk away, although I kept my back to him. Maybe I shouldn’t have done, because now I can’t quite shake off the thought that he had kept walking towards the farmhouse. Towards Linda.

I reached into my pocket and took out a packet of cigarettes. Linda wouldn’t let me smoke in the house. I sparked up, inhaled, felt the nicotine surge through me. It seemed to cool the molten anger flowing through my mind. I blew out the first lot of smoke and watched it curl out into the chill autumn air.

I looked out across the field. The freshly drilled earth ran away from me in shadowed diverging lines. I glanced leftwards, hoping to see it. The woods stared back, impassive. I watched as the breeze stirred the old oaks and beeches. For a moment I wondered how long they had been stirred by that breeze, and for how much longer. I realised I was on the edge of something I didn’t and couldn’t understand, and I backed away from it.

Then the sparrowhawk burst forth from the trees, scorching low over the sod, a blur of light brown upon dark. I watched as it made for the hedge on the field’s furthest side, missed its prey, and lifted up over the hawthorn. I stood there, my muscles suddenly seized up as if by cramp, and stared at the spot where I had last seen it. With all my will I desired it to return to that spot, to see it frozen in time, to witness once again its beak, its talons, its soaring wings.

I stood there until it was dark. The hawk did not return. By this time I was shivering, my teeth rattling away. I left the field and walked up the lane as fast as I could. For a moment I wondered what the hell I was doing. I knew my behaviour would have seemed strange to Adams, to Linda, to anyone.

But it did not seem strange to me.

I had to see the hawk. It was a perfectly natural desire.

Sunday

I woke up this morning still shivering. Although embers still smouldered in the grate, I was cold. I put my hand to my forehead. It felt hot and damp. I groaned, and got out of bed.

I was still shivering as I walked downstairs, even though I had two jumpers on. I glanced into Linda’s room, its neatness the opposite of my own. That was Linda, through and through. Neat. Clinical.

She was boiling eggs on the stove. “Are you alright?” she asked.

“Fine,” I growled through teeth I had to keep gritted so as to stop them chattering. “I’m going out.”

“But breakfast…” she began.

Ignoring her, I took my coat off the peg and with Sonny at my heels, stepped out into the yard. It was a crisp autumn day, the sun not quite up yet. I breathed in the cool air and felt a little better. From somewhere a shotgun blast sounded, but I thought nothing of it.

After a few moments, I crossed the yard to where the hose lay. I began washing down the grain trailer, and after half an hour I had stopped shivering and instead was far too hot. I swore, and caught Sonny scampering past. I sprayed him with the hose, laughed as he went cowering away.

“What’s the dog done then?” said Ted, rounding the corner. “Bitch in heat somewhere?”

I dropped the hose. “Get this clean,” I told Ted.

He touched his hand to his cap. For some reason, today he looked even more untrustworthy than usual. I hated him. The natural thing to do was hate him. It seemed strange to me that I hadn’t realised that before.

He couldn’t meet my gaze. “Right you are,” he muttered, picking the hose up. “Where are you off to then?” he called as I walked away.

I ignored him, ignored Linda as she appeared at the farmhouse door and called to me.

I hated all of them. Hated everyone. Hated the world.

I wanted to be the sparrowhawk.

As I walked up the lane I thought of my dream, wished that it could become reality, that I could somehow leave this life behind. If I was the sparrowhawk, I wouldn’t have to worry about Ted, or the farm, or debt. I wouldn’t have to drill all the fields singlehandedly. I wouldn’t have to drill them at all.

The wind gusted as I made my way up the lane. I felt suddenly light-headed, and then light-bodied. The wind might carry me away at any moment. I stumbled trying to step round a pothole, and when I regained my footing it was as though something had suddenly changed. The light-headedness was still upon me, and the feverishness, but they did not seem to matter.

I felt suddenly outside, above everything. I was beyond rules, beyond the law, beyond it all. I could do whatever I wanted. I smiled.

Pushing open the gate to the field, I scanned the freshly turned earth. There was something out of place on the ground.

I squinted. Groaned. Ran as best I could to the middle of the field, labouring over the soft soil. I knelt beside the body.

Its killer – of whom there was no sign – must have been very close. The shotgun blast had taken off most of the right wing. Only a tattered, bloody stump remained. The large, pale orange eyes were filmy. One of them was pinched half-shut, pathetically, like an old man trying not to fall asleep. The chest was spattered with blood.

For a few moments I could not understand what had happened. I looked at the dead sparrowhawk, and tried to join it to reality. I put my fingers to the stump where its wing had been. My fingers came away bloody. I raised them to my lips, tasted the saltiness of the blood, and then I realised that what I was seeing had happened.

Someone had killed the sparrowhawk, had left it to rot in the middle of my field.

And I knew who.

I understood the lightness of my head and body now, understood the rage, the blood-lust. I had always been connected to the sparrowhawk in some way, had shared an element of its soul. Now that it was dead, all its qualities were mine.

I stood up, spread out my arms, imagined the wind ruffling the feathers of my wings. It was time to hunt. Bending down, I picked up the battered corpse and cradled it in my arms. The arms and chest of my coat became smeared with blood, but I didn’t care. Things like that did not matter anymore.

Adams’ farmyard was clean and tidy. His nice shiny tractors were all lined up under the cover of a three-walled barn. It was still quite early. They hadn’t begun work yet. That suited me.

The first person I saw was a young lad sweeping up loose straw and spilt grain. No wonder the yard was so spotless. The lad looked at me as though I was mad. He was mistaken. He was the mad one. I knew just what I was doing. Filled with clarity of purpose, I smiled at him. His eyes fixed on the dead sparrowhawk, he did not smile back.

“Where’s Adams?” I asked.

He pointed wordlessly towards the workshop. Thanking the lad, I made my way over. My head felt as though it were floating. For a moment I saw myself below, stumbling unsteadily towards the workshop, a dead bird in my arms, and I realised why the lad hadn’t spoken to me. Then I returned to my own mind once more. Everything was all shivery, and my legs felt weak, but the hunt was on, and I could not falter.

“Adams!” I called once I reached the closed door of the workshop.

The door opened, and Adams stood there, framed against the murky interior. He frowned. “Dan? You alright? You look awful.”

I didn’t reply. Just laid the dead sparrowhawk gently at Adams’ feet. I took a step back and wiped my brow.

Adams frowned again. He looked at the hawk. “Is that the…?” he began. “The hawk you were watching?”

I shook my head, laughed. “Don’t try and act surprised, you fucker.” I took a step forwards.

He raised his hands up. “Dan, I don’t know what this is—”

I hit him then. All my rage, my fury – at him, for being successful, for most likely sleeping with Linda, for his smugness, at myself, for everything – was released in that punch.

He moved too quickly though, and I only caught him a glancing blow on his arm. Off-balance, I could do nothing as he shoved me away. He stepped forward, grabbed my arms. I tried to wriggle away, but he was too strong. “You cunt,” I spat, spraying out blood. I had bitten my lip.

I wanted him to be angry. Wanted him to hit me, so I could hit him again. But he didn’t. He just pinned my wings to my sides, looked into my eyes.

“You’ve got a fever, Dan. You’re not well. You should go home. Go back to Linda. I didn’t kill the bird.” He spoke slowly, steadily, and I could tell that he was trying to hold in his anger after all.

“You did,” I growled. I tried to shake free, but he was too strong. “You did. And I know what you’ve been doing with Linda, too.”

“Doing with Linda?” he repeated. There was a moment’s pause. Then he laughed. “You really are pathetic, Dan. I went to your house the other day to tell her I was worried about you. That’s all. I feel sorry for your wife, but that’s it. Keep still.”

He called across the yard to someone else, and soon was joined by one of his workers. They frogmarched me across the farmyard.

“I’ve tried to be patient with you, Dan, I really have,” Adams was saying. His words seemed to come from far away, from far below. “You haven’t had it easy, specially not the way your dad was. But this is too far. Too far. Let him go, Jack,” he said to the other man.

Adams kept his hand on me for a moment longer, then he shoved my out into the lane. “Go home, Dan. Go to bed. I didn’t kill your fucking hawk.” He and the other man turned away and walked back into the yard. I watched them go, and then went up the lane.

I stood by the field. My legs felt weak, and I had to lean against the gate for support.

I had never felt so useless, so pathetic. The red fury that had been in me was gone. I was no longer the sparrowhawk. However much I tried to pretend it wasn’t so, I knew one simple truth. The hawk would never fly again, and I could not live within false dreams.

The autumn sky above was grey, full of secrets in comparison to the awful truths I was surrounded by. I kept looking up, hoping that I would, by some miracle, see another hawk. Nothing came. All I saw were a few crows, chattering away. I watched them fly out of earshot and then out of view. Still I kept looking up, until my neck began to hurt. At least I no longer felt cold.

Adams was right. He hadn’t killed the hawk. I could see that he was telling the truth.

The words came to me unbidden.

Pests, in my view. Waste of space.

Pests, I thought. Pests.

In those moments, I saw it all. Understood. I knew why the hawk had mattered, why it had died.

I knew what to do.

Ted would come this way. I didn’t know when, but he would come.

I would take all the sparrowhawk had taught me. I would inherit what it had left.

I crossed the field and went into the woods. I moved into a dense patch of browning ferns. Dropping to my belly, I lay there, my face to the ground, feeling the wood around me. I suddenly felt aware of every tree, everything that moved above them, beneath them. I was aware of it all. I sensed everything. Knew my place amongst everything.

I would burst forth from the ferns, keep low, and strike. The last thing my prey saw would be my face. Ted hasn’t come back yet. But I know he will. He has to. And I will be waiting.