Anyone Can Cook. Anyone Can Review.

Illustrated by Samantha FultonIn her essay ‘How Should One Read A Book?’, Virginia Woolf puts forth the idea that ‘the quickest way to understand the elements of what a novelist is doing is not to read, but to write; to make your own experiments with the dangers and difficulties of words.’ The impulse of a reader to fashion a text according to their own terms is what makes literature such a unique discipline. After all, the immediate reaction one has after reading a book is to discuss it (or tear it apart) —whether this be through conversation or online. Responses to texts may differ greatly, and this sort of disagreement is completely acceptable — in fact, literature encourages it. In an online age where people are free to express their thoughts on a global scale, everyone can be a critic.

Yet, because of this, reader reception and its impact on literary value is becoming an even more contested site than it already once was. Whilst Woolf is of the opinion that an independent reading is eternally valuable to the reader, this overestimates the extent of autonomy readers exercise over their interpretations. Of course, this argument seems logical: after all, the only person capable of judging whether or not they like a book should be the reader.

Yet opinions are fickle and are constantly susceptible to influence, and Woolf’s plea for literary independence seems a far-reached ideal. Before someone reads a book, the likelihood is that they will approach it with an unconscious internal bias. However, this begs the question of whether the Internet is increasing this bias. The book may have been recommended on social media where people were raving about it for weeks; equally, it may have been written by an auspicious author whose name is plastered everywhere on the net. All of these are factors that subconsciously shape our opinion towards a text.

The ever-expanding tentacles of the world wide web also means that the nature of criticism is changing, and literature needs to catch up. Caleb Crain, writing for Harper’s Magazine, observed how the rise of online reviewing has threatened literary value: ‘Most reviews today, cut off from communities that once fostered and disciplined them, have no authority.’ Whilst I acknowledge Crain’s claim that literary value may be affected by amateurisms, his disregard for the average reader’s opinion seems unfairly elitist. Sure, the nature of applying an opinion is hierarchical as one perspective may be considered more informed when set against another, nevertheless, it is impossible for one person to claim absolute authority over a reading, an activity which is intensely subjective.

Online reviewing also poses another question that Crain highlighted: are algorithms affecting the way we read? Much like how social media sites filter content accordingly, certain pieces of literature may only be granted a glimpse on retail or reviewing websites because of a sequence of code. Crain’s dismal perspective on algorithms and the literary market seems to be a digitalised, and perhaps even crude, version of evolutionary Darwinism where one set of data strives to triumph over another. Yet his assumption that readers rely solely on algorithms to discern literary value underestimates their competency. Whilst readership did increasingly align with consumer culture from the eighteenth century onwards, long-term value rarely stems from flash surges of retail popularity, and the literary market’s shift towards the Internet will not change this.

Ultimately, online literary visibility should not be demonised. I, for one, would prefer to live in a literary democracy on the Internet where I am free to encounter a wide range of opinions and formulate my own perspective on them rather than defer to a small sect of the literary elite. So, whilst the nature of reading has changed in the past century because of the Internet, and readers may find it increasingly difficult to adhere to Woolf’s plea for independence, this has fostered another completely different and much more enriching phenomenon — a dialogue between people across the globe. In light of this, here are a few online reviews that I found particularly entertaining.

A review on Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis:

Source: Goodreads

A review on Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights:

Source: Goodreads

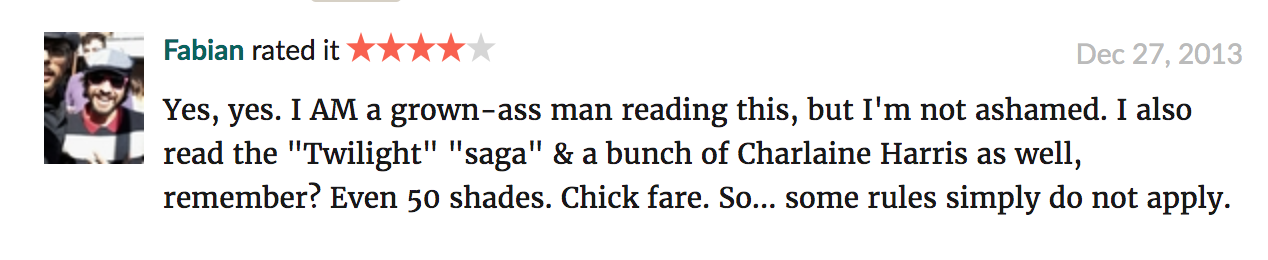

A review on Louise May Alcott’s Little Women:

Source: Goodreads